Taking weighty decisions for a safe and liveable country

No stable delta without delta design. Professor of Delta Urbanism Chris Zevenbergen advocates a revaluation of spatial design

Subsidence, salinisation, climate change, population growth, social dichotomies and dwindling resources. Nature systems and societies in urban deltas around the world are struggling. The Netherlands is no exception and, for this reason, professor of Delta Urbanism Chris Zevenbergen is making the case for greater imagination in science and public administration. “We need to be able to believe in the future.” On 2 December 2022, he gave his inaugural address.

From 1999 to 2012, Zevenbergen was director of innovation at the construction company Dura Vermeer; during this time he put water management on the construction sector’s agenda. “Twenty years ago, relatively little attention was paid to flood risks in urban areas. As a construction company we soon found common ground with knowledge institutions and government bodies that wanted to map out flooding and flood management in cities. The emphasis here is on limiting the effects of floods, not preventing them. What this requires is the creation of resilience, a term that has since become commonplace in the discourse on climate change. How do you do this?”

We need to be able to believe in the future.

Redesigning Deltas

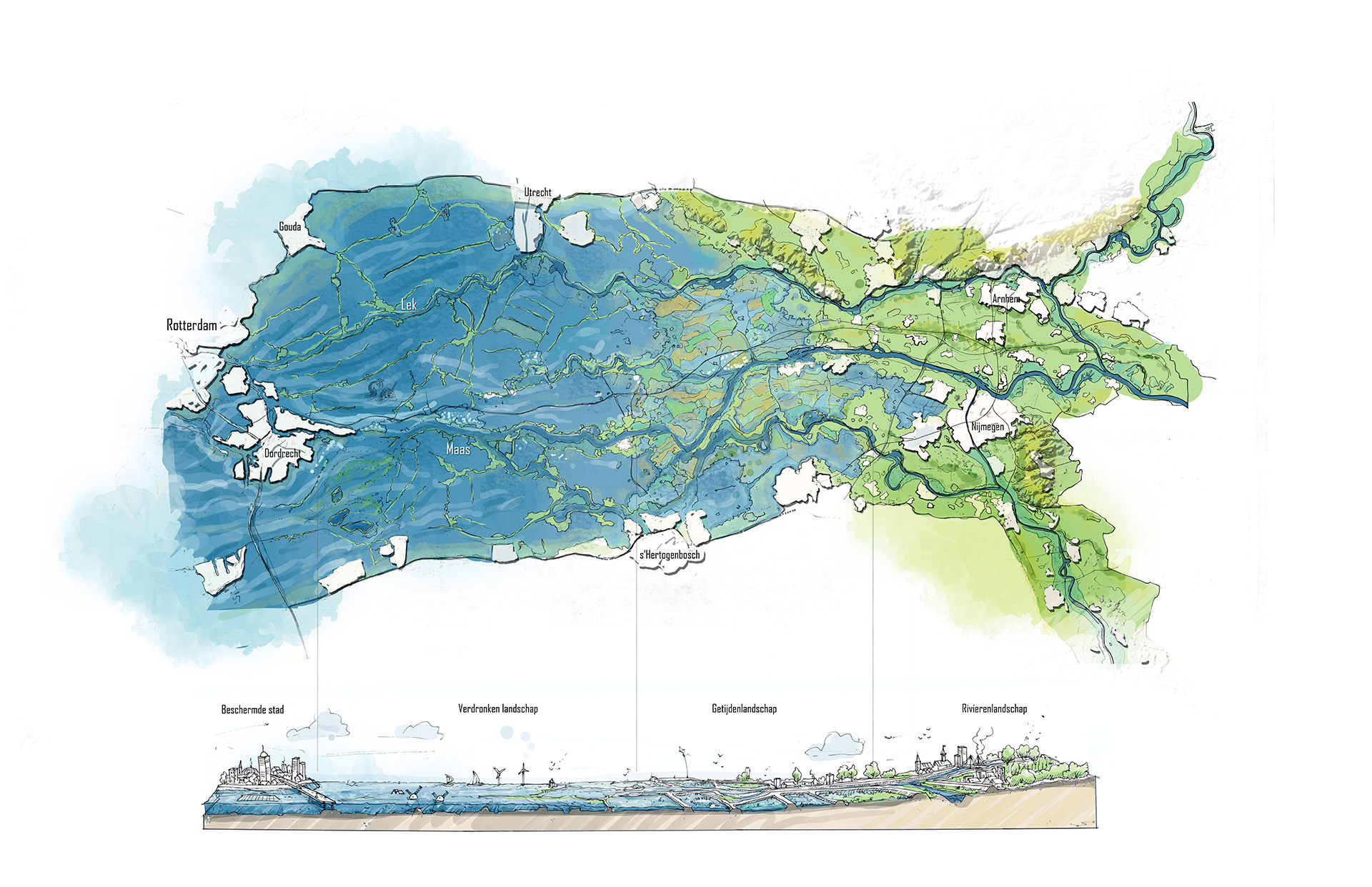

For Zevenbergen, practice and theory often go together. From these solid roots in the business world, he joined IHE Delft Institute for Water Education in 2005 as professor of Flood Resilience. This is a position he still holds part-time to this day. A second part-time professorship followed in 2020, with Zevenbergen following in the footsteps of Han Meyer, professor emeritus of Urban Design. “Thanks to Han Meyer, designing research into the spatial development of urbanised deltas gained an established position at TU Delft under the name Delta Urbanism.” As professor of Delta Urbanism he now leads a research programme called Redesigning Deltas, which is devoted to the question of how densely populated deltas can remain safe and liveable even as climate change and further urbanisation put increasing pressure on landscapes and resources, and obsolete infrastructure calls for replacement. “How must this all be managed in the longer term? What course should one adopt? How do we arrive at new, well-substantiated plans and investments? As a collective and interdisciplinary effort, spatial design is a valuable strategic instrument. Hence, other faculties, knowledge institutions and the professional field are closely involved in the implementation of this programme.”

If you want the country to be safe and liveable in the long term you will have to take weighty decisions in the short term.

Making decisions

After his appointment, Zevenbergen took the time to talk to all those involved to get an idea of the position of designing research in spatial design in the Netherlands. “The authority this type of research has and the knowledge it generates has taken a considerable knock.” Whereas in the Room for the River programme the question of securing spatial quality was seen in conjunction with water management measures, funds have since then been allocated for water safety in a much more efficient manner.” Yet proper spatial design as a breeding ground for considered spatial planning is sorely needed, Zevenbergen pleads. “In the past ten years, the policy was to modify and adjust in tiny steps. However, the system is less predictable and manageable than we thought. Consider the uncertainty surrounding the rising sea level, for example, or the multiple droughts of recent years. Consider nitrogen, and what havoc it has caused.” The time for patching and mending seems to be over. According to Zevenbergen, far-reaching decisions about the configuration of the Dutch delta need to be made in the next few years. “There is a realisation that if you want the country to be safe and liveable in the long term you will have to take weighty decisions in the short term.”

Imagination

The need to anticipate an uncertain future brings Zevenbergen to the role of spatial design as a matter of course. “Modelling reality and making predictions on the basis of this has its limitations, as we have seen. An approach that extensively rationalises the interplay between physical systems and society and then takes risks on the basis of this, is too one-sided. To be able to investigate and check transforming scenarios we also need imagination.” To illustrate this, Zevenbergen mentions that roughly ninety per cent of investments in the development of urbanised deltas are not climate proof. “Spatial design generates imagination and is able to integrate spatial interests and functions in such a way as to allow engineers to actually start calculating scenarios. A challenging but well-substantiated vision of the future can act as a source of inspiration, as a touchstone and as a quality impulse for the formation of strategy.”

Solid footing

The future strategies for five Dutch regions recently developed under the Redesigning Deltas umbrella illustrate what a functioning delta might look like in 2100. “The question is whether one would ever have sufficient information to be able to predict what a large part of a country will look like in the distant future. And yet, painting possible development paths on the basis of the past as well as on images of a far-off future – forecasting and backcasting – definitely gives one a more solid footing.” At the same time, rather radical images of the future also elicit resistance, Zevenbergen notices. Collaborating in multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary fashion is very difficult. “People are not necessarily open to thoughts or ideas that do not align with their own beliefs and values. Some scientists withdraw into their familiar discipline. We also notice that civil servants simply do not have the time to really study and get to grips with the subject matter.”

Delta science

Informed consideration of the future is not only a skill in itself, it also happens to be a sensitive issue because in complex societies spatial development touches on a great number of interests. To be able to properly grasp the complexity of urbanised deltas and to make sense of them, you need a new type of science, says Zevenbergen. “What is needed is a delta science that integrates and complements the social, natural and behavioural sciences. This will involve delta designers who unite culture, behaviour, nature and technology and reintroduce imagination into science and planning. This must enable rational analysis to go hand in hand with understanding of and insight into the more intangible aspects of our complex society. We need to be able to believe in the future.”

Further information

On 2 December, Chris Zevenbergen gave his inaugural address, which can be watched here.

More information about Chris Zevenbergen of the department of Urbanism can be found at professors page.

Read the full article about the future strategies that was recently published by TU Delft here.

The images included with this interview are from Redesigning Deltas, a program initiated by the Delta Urbanism research group under the direction of Chris Zevenbergen of the Department of Urbanism at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment.