Modeling irrigation in ancient Americas

Ancient irrigation has had its fair share of studies, particularly on canals on the Peruvian North coast. Despite this valuable research, how the irrigation systems underlying the ancient civilizations may have functioned, is not clear at all. In this project, I study how irrigation systems on the Peruvian north coast developed as emerging anthropogenic landscapes from the purposeful but uncoordinated activities of individuals, households, and small groups. Despite its arid environment, ancient civilizations have prospered on the Peruvian coast. The narrow coastal plain is a desert with river valleys separated by areas with little or no vegetation. The rivers flowing from the Andean mountains to the west provide the fertile coastal valleys with irrigation water. The valleys are oases, and exploitation of their agricultural potential depends on irrigation, although some small, highly productive areas do not require irrigation. Irrigation canals diverted (part of) the water available in the rivers. Some canals had two intakes, with one being used when the water level in the river was low. The river water level was probably raised to divert water into the canal by means of stone and brush weirs. Peruvian conveyance canals could be rather long and often required aqueducts to pass small side valleys. Sometimes canals were cut into rock in order to maintain the grade. Canals were frequently stone-lined, others became lined with the clay sediments in the irrigation water settling in the canal.

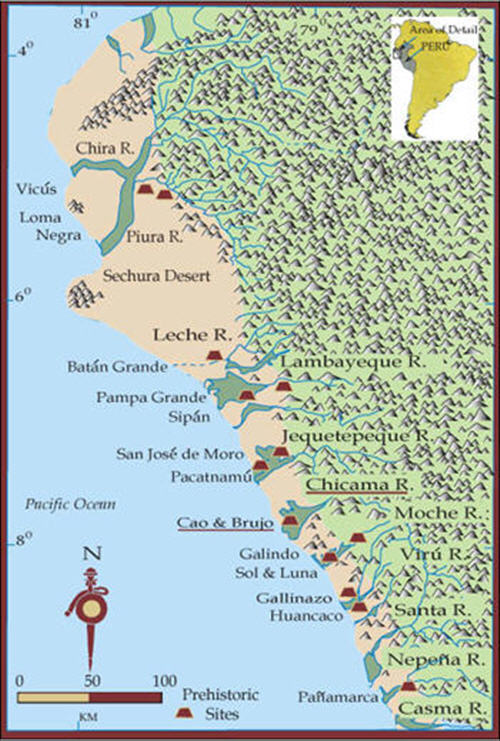

Map of Peruvian Coast (from this site)

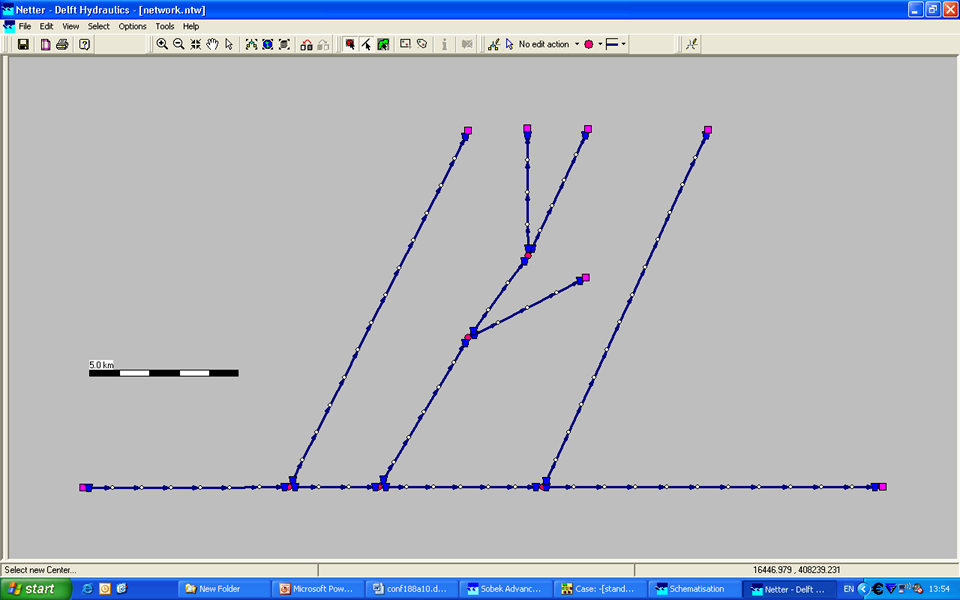

The intense debate on hydraulic calculations for pre-Colombian canals shows the need for good data, but also for well-based hydraulic assumptions, calculations and modeling. Most hydraulic calculations available have been based on assumed uniform flow conditions. Due to canal dimensions and variable flow patterns, however, uniform flow may have been the exception in the canal systems under study. For individual canals, especially the longer ones, for example for the Chimu Chicama-Moche Intervalley canal, uniform conditions for some or even most of their length can be assumed. For shorter canals, particularly in networked systems with structures, assuming uniform flows would not be correct. The mathematical formulas describing non-uniform conditions cannot be solved analytically and require numerical hydraulic modeling techniques. Hydraulic modeling supports studying how physical properties of systems can be understood and brings up new questions on the irrigation systems under study.

Are you interested in finding out more about this project, or working on part of it as a BSc. or MSc. project? ContactMaurits Ertsen.