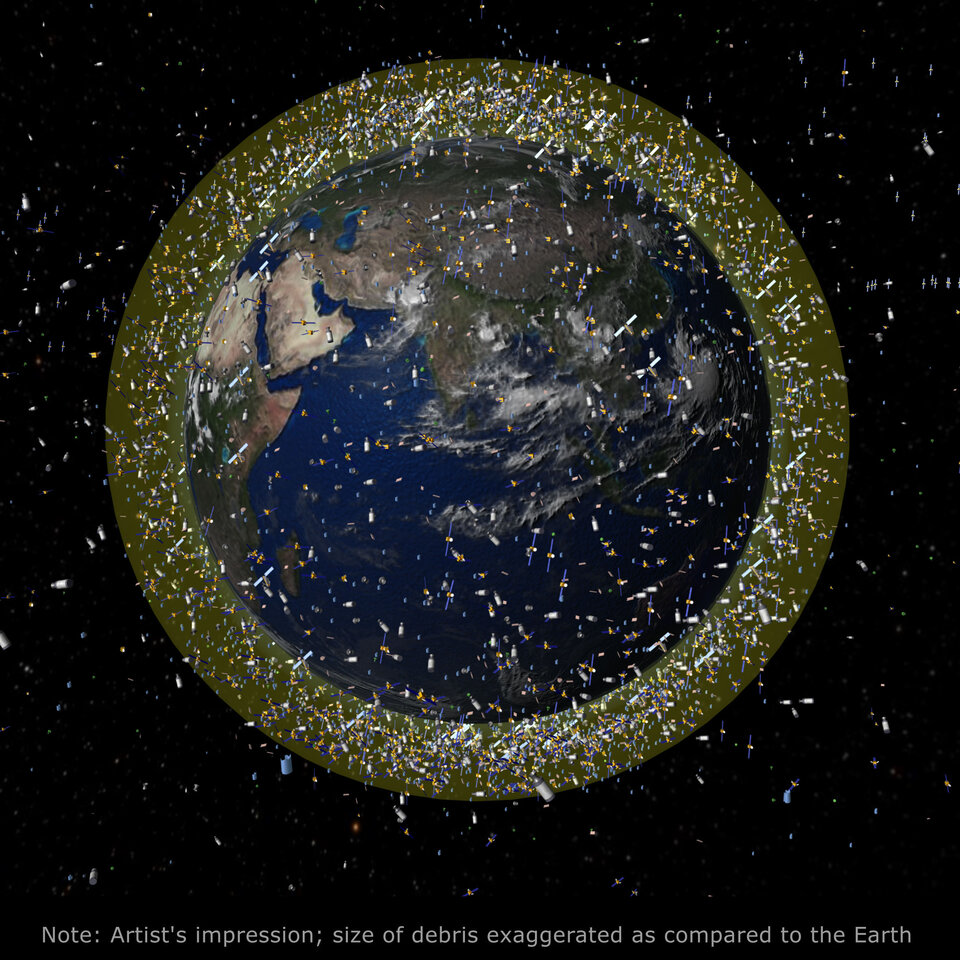

“When ice melts in Greenland and moves to the sea”, Riva, associate professor at the TU Delft Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, explains, “there’s less weight over the land, so Greenland comes up. But it isn’t just Greenland, the regions surrounding it also lift up. This is something that has been known for a long time. But such a slow and large-scale vertical land motion, as seen by GPS stations moving up or down, is something that we’ve been only able to measure for the last 20 years or so through satellite observations.”

In an article from 2017 in the journal The Cryosphere, Riva and colleagues modelled how much of these vertical land motions, which happen globally, are caused by melting ice. “We have known about this effect for a long time, but people have disregarded it because they thought it wasn’t large enough to be relevant. Nowadays, we know much better how much ice is melting in Greenland and the glaciers, and how much ice is melting in Antarctica. So I thought why not model it, and see how big the effect is and whether we should take it into account when interpreting sea-level change observations.”

The effect is certainly not insignificant. According to Riva’s calculations, between 1902 and 2014, cities in the Northern Hemisphere, such as Rotterdam and London, lifted up by about 4 cm due to continental ice mass loss alone. Cities in the Southern Hemisphere, such as Rio de Janeiro and Sydney, subsided by 1.0 and 3.4 cm, respectively.

Water moving South

“There are 3 effects”, Riva explains. “One effect is land lifting up close to where ice is melting, because there is less weight on the lithosphere, the solid outer part of the Earth, which can then rebound like a spring. Another effect is when the water moves to the ocean, there is more mass there, and the ocean bottom deforms – it goes down. But also, if there is less ice on Greenland, then Greenland attracts less ocean water, because of Newton’s law of universal gravitation. So, if Greenland gets smaller, ocean water also goes away from there, and it goes away as far as possible.” That’s why most of the subsidence is in the Southern Hemisphere. Australia and New Zealand, in particular, are the farthest locations from all the melting ice sources, and where the water moves to.

This is good news for the Netherlands, but bad news for islands in the South Pacific Ocean. “That’s why people worry so much about Antarctica in the Netherlands,” Riva adds, “because then the story reverses.” If Antarctica melts, then the water will move North and there will be direct effects on sea-level change in the Northern Hemisphere. Although there is some uncertainty, Antarctica is not currently melting as much as Greenland.

Open data

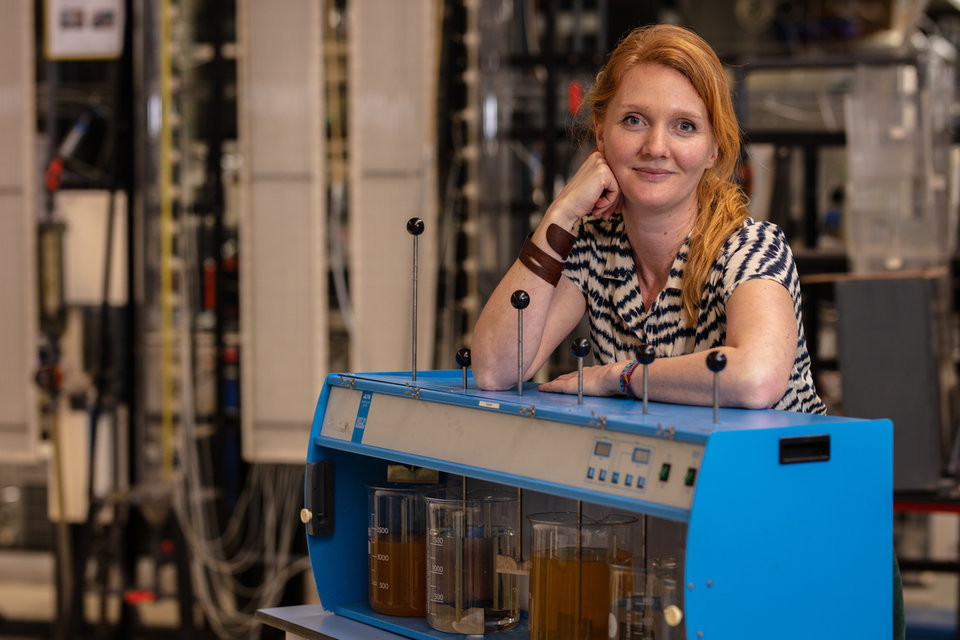

For his MSc and PhD research, more than 15 years ago, Riva studied earthquakes using GPS data. “Even then, I was already involved in modelling Earth deformation, by comparing models to GPS data.” He was disappointed that he couldn’t access data that other groups were collecting. “Sometimes, I could not verify my results, because the data belonged to someone else. That was really frustrating. When data are open, then anybody can use it. There will be some competition, but that’s only good. Competition leads to new ideas, which in turn lead to even more ideas and to progress in science.”

The data used to generate the figures in Riva’s current paper were made publicly available through the 4TU.Centre for Research Data with the support of the TU Delft Library Research Data Management department. Riva: “I believe that sharing data helps progress in science and that if you get public money to do research, then the results should be public. Many journals nowadays require to publish datasets used in scientific paper in open access repositories. It is positive that this is becoming the standard.”

“Melting ice is a hot topic in research. There is so much we don’t know yet about the earth system. For example, about the effect on the solid Earth of the past glaciations or how the ice sheets interact with the oceans and the atmosphere. There is a lot we need to understand, only to understand sea level rise, and that is what drives me as a scientist.”