When the time comes for autonomous cars to hit the roads, they’ll have to take other road users into account. For example, they’ll need to stop when a cyclist abruptly turns. Laura Ferranti is studying how this can be best achieved. Even when roads are packed with traffic.

Imagine, you’re driving your car through the centre of Delft, guiding the vehicle along the picturesque canal-side houses and over a quaint bridge. Before you turn off, two cyclists speed by at the last moment. After they’ve passed by and you want to accelerate, a father with a pram quickly crosses the road just in front of you. This isn’t an unusual scene in the busy centres of Dutch cities. Road users are used to it by now.

“But these situations are extremely difficult for technology to figure out,” says Laura Ferranti. She’s a researcher at the Department of Cognitive Robotics at TU Delft’s ME Faculty. “How does a car know exactly when someone is about to cross, and how do you make sure you notice all those two-wheelers speeding by? These are obviously things we need to sort out if we want to make a car that’s nearly or completely autonomous. At the same time, you don’t want the vehicle to remain stationary all the time just because it’s afraid to move in any direction whatsoever as a result of all the other road users.”

Robots and humans working together

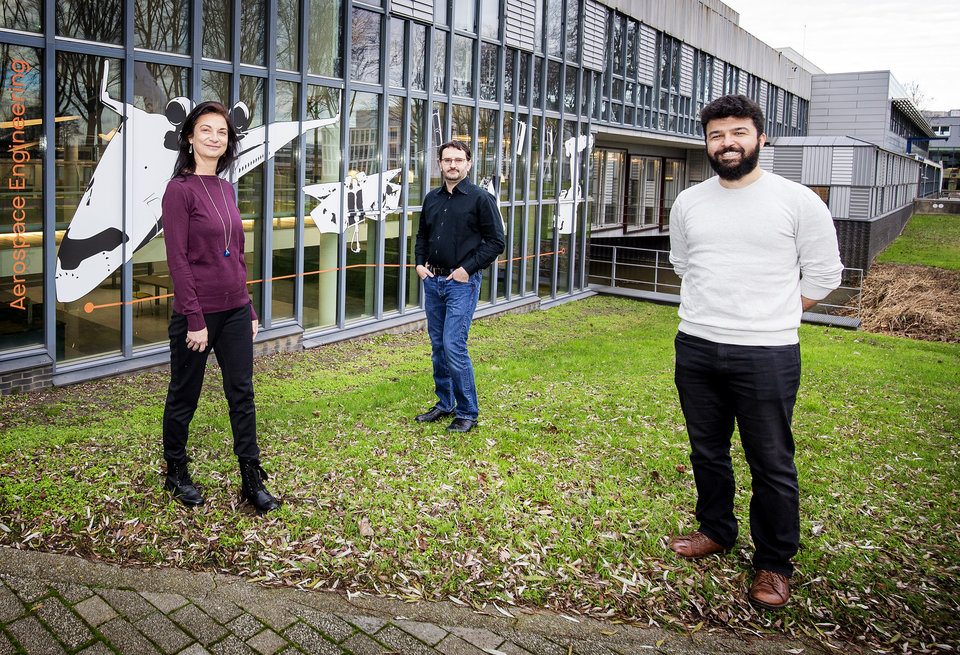

That’s why Ferranti is working on solutions with colleagues from Dariu Gavrila and Javier Alonso-Mora’s team. They’re developing technology that will allow vehicles to detect everything around them and know when they can and cannot accelerate. So it’s a technology of the future. You could view this kind of autonomous car as a driving robot. In recent decades, robots were usually hidden behind the high walls of factories, where they assembled electronics, for example. “But the new generation really must work together with humans. It won’t be long before we see these robots on our streets.”

They estimate whether a pedestrian will cross a road or a cyclist will make a turn and precisely when. They do this using sensors, such as cameras and GPS that tell the vehicle where these pedestrians and cyclists are. We use that information to estimate the car’s possibilities. We want to determine which routes the car can take to safely reach its destination

This means that vehicles will be constantly predicting which route is the safest to follow. “They estimate whether a pedestrian will cross a road or a cyclist will make a turn and precisely when. They do this using sensors, such as cameras and GPS that tell the vehicle where these pedestrians and cyclists are. We use that information to estimate the car’s possibilities. We want to determine which routes the car can take to safely reach its destination.”

To achieve this, you to have an accurate idea of what people are going to do and how to process this information in order to safely continue driving. The car’s system interprets this, as it were, by reading body language, posture, movements and the direction a person is going in. A cyclist who looks over his shoulder a few times and then sticks out his hand is easy to notice. But someone who turns the handlebars with no warning isn’t. Still, the car has to take both into account.

Predicting the unpredictable

“Ultimately, several (partly) autonomous vehicles will share this information with each other in the future,” Ferranti says. In addition to cars, it will also include ships and drones delivering packages. The idea is to make things safer by sharing information. Another vehicle may have a better view of road users, which will help your car make the most accurate estimation possible. “The vehicles also communicate where they are going. So if you make a turn, other road users will receive that information as well. So you’re helping each other.”

Vehicles will therefore continuously communicate with each other. This must be done in a safe and responsible manner, says Ferranti. “As researchers, we ensure that vehicles will drive, sail and fly safely in the future. But it’s also important to think about privacy. A great deal of data is being collected, and we take images of other road users. Safety is also important. You have to make sure that everything is well protected. We’re already thinking about this as well.”

As researchers, we ensure that vehicles will drive, sail and fly safely in the future. But it’s also important to think about privacy. A great deal of data is being collected, and we take images of other road users. Safety is also important. You have to make sure that everything is well protected. We’re already thinking about this as well.

This technology is still developing, so the autonomous car is still a vision of the future. The fact that Ferranti is working on the traffic of the future is not entirely coincidental. She used to be fascinated by the roads in Rome, where she was born and raised. “The traffic criss-crosses all over the place there. Cars switch lanes at a moment’s notice, scooters zigzag in between everything, and then there are the pedestrians who cross whenever they please. It’s a nightmare for traffic experts. At the same time, it’s also very interesting. Because in the future, autonomous cars are going to have to learn to read and understand these kinds of situations too. I often think about this during my research.”

This practical approach characterises Ferranti’s method as a scientist. She started out as a researcher who liked to focus on theory. “I enjoyed working on abstract problems and made many calculations. Now I focus on realistic and practical problems: how robots can safely move around humans . Suddenly, very different uncertainties come into play. It’s much more complex. That’s why I found it a bit scary at first. But that has changed in the meantime. Now, working on real problems and trying to solve them appeals to me. But the field of research remains exciting, because you’re trying to predict something that’s quite unpredictable.”

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/_processed_/0/b/csm_Header%20afbeelding%20InDetail%20-%20Stefan%20Buijsman%20-%202_01_8b72583971.jpg)