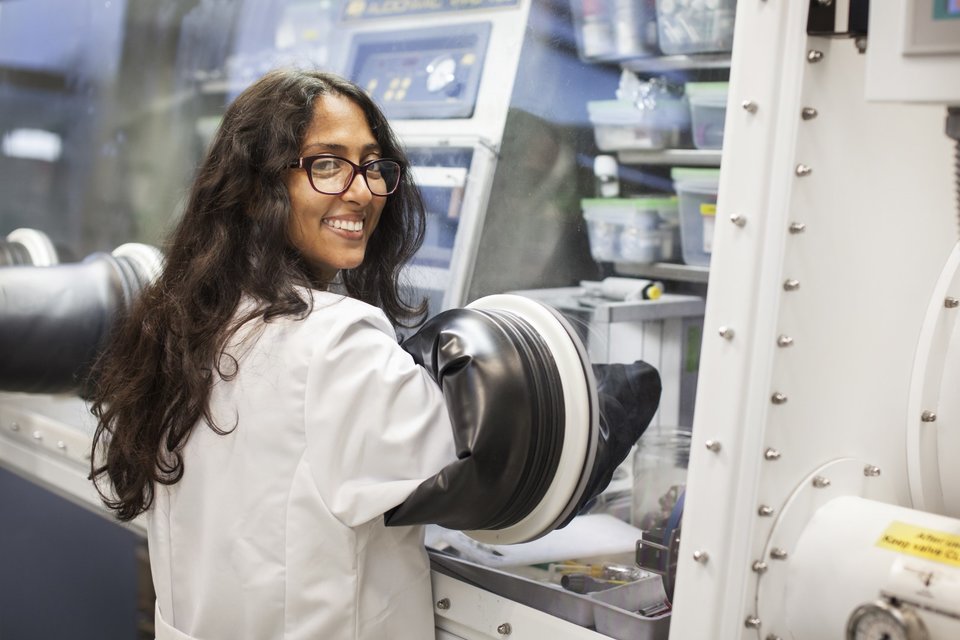

Steel is indispensable in our modern society. We use steel every day: in bridges, cars, vessels, trains and apartment buildings, but also in cutlery, bicycles, batteries and locks. Unfortunately, its production releases a lot of CO2. For years scientists are doing research for developing a good alternative. But due to steel’s large-scale functionality we have not managed to find a good alternative yet. Also it will take some time until we do. But it can be done! This is what TU Delft scientist Yongxiang Yang says. For decades, he has been fascinated by methods for greening steel.

‘Steel is one of the most important materials ever. Everyone is familiar with the stone, bronzeand Iron Ages. In the last 150 years, steel has become so important that I call this the Steel Age,’ Yang says. He knows what he is talking about. TU Delft has been collaborating with Tata Steel for a long time, with master’s and PhD students doing part of their research at the company. Yang is group leader of Metals Production, Refining and Recycling at the ME faculty.

In the last 150 years, steel has become so important that I call this the Steel Age.

The current method of producing steel also has considerable disadvantages, Yang immediately concedes. For example, many polluting substances such as the greenhouse gas CO2 are released during production. In the Netherlands, steel is produced at Tata Steel in IJmuiden, and with the processes currently in use, the company is also one of the country’s biggest polluters. Moreover, people living near their plant suffer from health problems.

New way of producing steel

But there is a solution, according to Yang. Together with other scientists, he is working on another pathway for producing steel. ‘This makes it possible to considerably reduce the emission of harmful substances. It will enable us to keep using steel as a key material for all kinds of vehicles, bridges, houses, packaging and many other applications. But there will be much less pollution. We have been working on this for decades. It is my green dream to make this happen,’ he says.

This is a new way of producing steel. Today, this is still done with the help of extremely tall towers, up to 40 metres high, which is why they are called blast furnaces. Iron is extracted from the ore in these furnaces. This process releases, among other things, the greenhouse gas CO2 that contributes to global warming. In a second step, the iron is turned into steel, which again emits CO2.

‘It can be done differently by taking a cleaner approach,’ says Yang. This is called DRI (direct reduced iron). This green route is currently in development. Experiments are already well advanced in Sweden, among other countries, also on a pilot scale. ‘We are using hydrogen in this process to make hot metal and then steel, so we no longer need the blast furnaces.’

The green pathway

This is a much greener approach because there are no CO2 emissions when you produce hydrogen from a clean energy source, says Yang. In Sweden, they do it with hydroelectric power stations. ‘In the Netherlands, we can get electricity from wind farms at sea.’

The numbers involved are gigantic. ‘We probably need 1,500 medium-sized turbines (4 GW capacity) to produce enough electricity for the steel industry in a green way,’ says Yang. IJmuiden is located by the sea, which means there are good opportunities to transfer electricity from turbines at sea to the plant. ‘An alternative is to work with natural gas first, but that is a fossil fuel and so worse for the environment. This would be an option in an interim phase.’

It is no coincidence that Yang is researching a green route. He has been fascinated by metal production for some 40 years. ‘In the 1990s, I went from China to Finland to investigate more efficient production methods for metals. I found it fascinating because you come across metals, particularly steel, everywhere. From tin cans to skyscrapers. In the 1980s and 1990s, a lot of research was still being done on making steel, but then many research groups stopped their work. There was this notion that this process had been fully developed, so it lost some of its appeal. Many of my colleagues were looking for other work. They went to work in computer sciences, for example, or concentrated on modern materials such as composites.’

Yang was not deterred by that, however, and wanted nothing more than to continue studying his favourite material. ‘Hypes are not really my thing, and I am a bit stubborn as well. Metals were not sexy at the time, but they still interested me. Even then I wanted to make it in a more environmentally friendly way. I saw a future in that.’

Environmentally friendly steel production

Already in those days, he came up with the technology to make this happen with colleagues and the Dutch steel industry. ‘In recent years, there has suddenly been much more of a focus on green steel, which has put the material back in the spotlight, much to my delight. It is important that we invest in sustainable solutions. It is my philosophy that we need to work towards a cleaner system with few or preferably no emissions.’

Yang also mentions other possibilities for producing more environmentally friendly steel. ‘There is a way to make steel by direct electrolysis. Scientists in Europe and the United States are already working on this. But that is not as far advanced as DRI with hydrogen. It is also possible to capture the CO2 and store it in empty gas fields, for example under the North Sea. There is no single route and no single solution, but there are several ways to produce steel in a cleaner way.’

He is optimistic about the future of steel. ‘There are promising long-term solutions. I see DRI in combination with hydrogen becoming commercially available between 2030 and 2050. The method with electrolysis will come into sight after that. Our aim is to produce carbon-neutral steel by 2050. That should be possible. I will be almost 90 years old by then. I hope I live to see it. In recent decades, I have seen major changes in the way steel is viewed and produced. I am convinced that we can improve things even more, and I will continue to enjoy working on this.’

Y. (Yongxiang) Yang

- +31 15 27 82542

- Y.Yang@tudelft.nl

-

34.H-2-190