The hospital consulting room has changed very little in the past twenty years. The digital age arrived in the form of the computer, but the screen literally came to stand between the doctor and the patient, with much of the doctor’s time and attention taken up by data entry. Now the computer sometimes feels like more of a nuisance than a benefit. “But computers can do so much more, and as doctors we all want the best for our patients. It’s in our genes,” says Joke Hendriks, vascular surgeon and head of the surgery department at Erasmus MC. So how can you incorporate digitisation in the consulting room of the future to make healthcare better? That is the starting point of ‘Consulting Room 2030’. This project is unique in that Erasmus MC, TU Delft and Erasmus University have been working together on it from day one.

The project was launched just over a year ago. “We asked a group of medical students and design students to analyse the daily practice in the consulting room. They talked to patients, specialists, insurers and legal and regulatory experts and came up with a ten-step process that starts with the run-up to the consultation and ends when the patient is back home again. This process became the backbone of the project. We can examine each of the process steps separately and identify things we can innovate or streamline with the help of technology,” explains Richard Goossens, Professor of Physical Ergonomics at TU Delft. “And we are looking at how can we change consulting rooms to help doctors do their work better, more efficiently and with more satisfaction,” adds Antoinette de Bont, Professor of Sociology of Innovation in Healthcare at Erasmus University.

A surgeon, a designer and a sociologist; this is precisely the kind of combination of knowledge that TU Delft, Erasmus MC and Erasmus University have in mind to tackle complex issues in sectors such as healthcare. For this to happen, various scientific disciplines will need to seek cooperation and even merge and converge. This is how it works in practice: “The first meeting I went to was attended by experts from different fields who all had an idea for using technology,” says De Bont. “For example, there was a dermatologist who wanted to use an e-health app to do something about the soaring incidence of skin cancer, but whose colleagues thought it would not be safe enough. Would a Randomised Control Trial help? Richard wanted to see the device, to see how well it visualised the problem, while I myself thought that you would not be able to inspire doctors’ confidence in a new technology with an RCT. We were forging connections between our institutions without being hampered by vested interests.”

This free exchange of ideas is essential. “We want to find the best solutions for the consulting room of the future. They have to be cost-effective, better for the patient, and improve healthcare in general. So there are many questions to answer,” says Hendriks. “It helps if you have all the relevant expertise at the table,” continues De Bont. “Joke knows exactly how a hospital works, Richard understands the technology and I look at it more from the system level. That makes us a good team to confront a problem like this. We feel free to talk openly; we don’t feel we have to turn every idea into a project. That gives us room to keep it light-hearted.” “This is because we have defined that higher goal of making healthcare better,” adds Hendriks.

Each their own questions

The goal is to improve healthcare, starting with the consulting room. They each enter this process with their own questions and expertise as starting point. “On the design side, there are very interesting questions that go well beyond the design of the technology itself. How can we ensure that the individual patient remains central, such that certain decisions or advice could be entrusted to virtual units, for example?” says Goossens. “How will the different patient profiles affect the design, such as elderly people who are less digitally literate? How do you adapt the operation of the device so that patients at home can use products designed for professionals?”

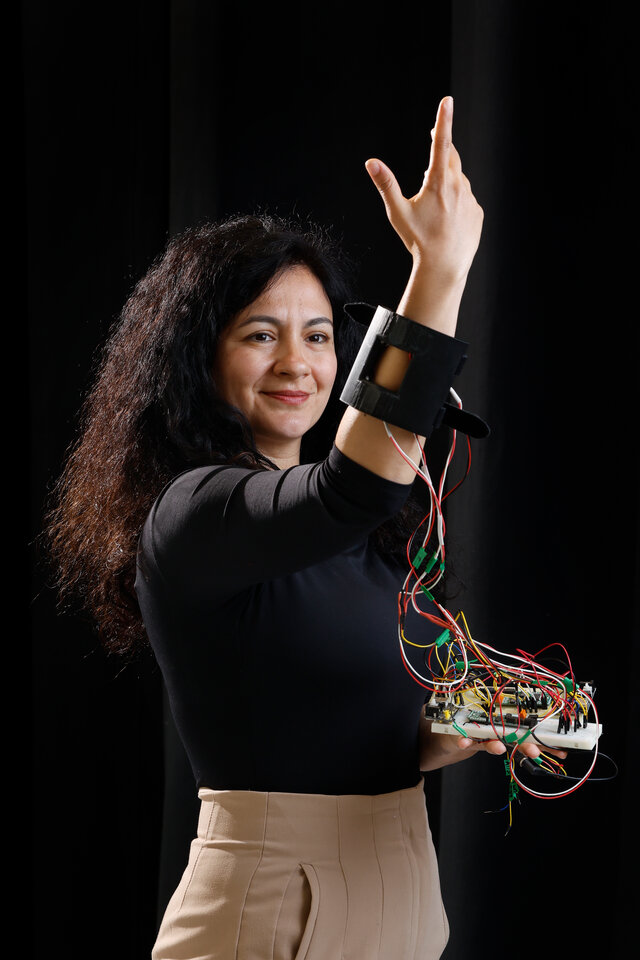

His students have already started pilot projects. “You want the data used in the consulting room during the consultation to be clear to everyone at a glance. But how do you present someone’s physical and mental state in an interface? One of my students came up with a circle that indicates how the patient feels mentally with a colour scheme, while the size of the circle describes how they feel physically. This helps the doctor to quickly see what kind of conversation they need to have. We now want to extend this principle to more variables.”

That touches on the questions that Hendriks is asking: “What are we going to do with data that patients generate in their own home? Should we use these data only in the consulting room, or shall we have an algorithm analyse the data even before the consultation starts? With a combination of precision diagnostics, patient risk profiles and home telemonitoring, we will be able to organise healthcare differently in future. This will allow us to discharge patients sooner, or monitor their condition digitally instead of them coming to a consultation. This means that the doctor will no longer wait reactively for a patient to fall ill and come for help, but instead offer proactive care in which the patient also has a clear role. Not everyone is willing or able to do this, so we need to be wary of creating a divide in society.”

De Bont looks at it all from the organisational level. “The hospital will ask questions like: ‘Who is going to evaluate the data?’ People will take on new roles; we will need to ensure that the nurses can operate the AI system and the doctors have confidence in it. At the system level, you will also have to look at the financial structure, because part of the hospital care that is currently the domain of the GP will now be provided at home using these systems. Moreover, our whole system is still based on paying an insurer more for insuring sick people. So the cost of healthcare is also part of the project. That is why we want to determine where we can best deploy AI, because if you can already provide a good diagnosis without AI then it may not have added value for this part of the process.”

Eye-openers

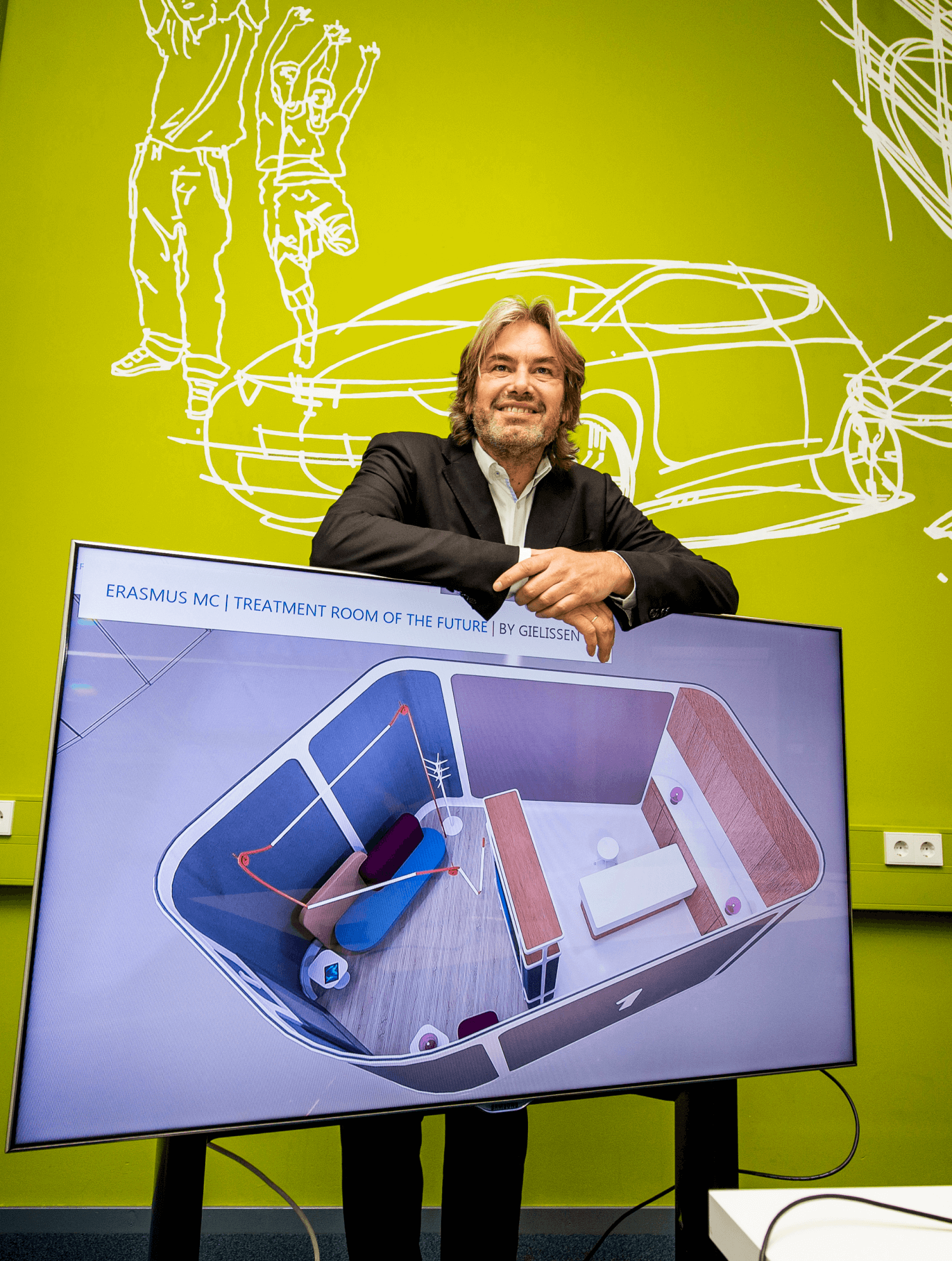

The team have been learning a lot from each other due to these different perspectives. For example, Goossens came up with the plan for a mock-up of a consulting room that will be installed in Erasmus MC in a year’s time. “It is not meant to be an end product, but an object we can use to test our assumptions. We call that research by design,” he says. “That was an eye-opener for me,” says De Bont. “You make a decision quickly, such as improving the consulting room with the help of software, and then you put all your effort into it. I would first want to understand the whole context. But starting with only limited information and seeing how it works in practice is a good way to get concrete results. That is also why the consulting room is being built, so that we can experience how it works. That idea of starting small I have learnt from you both. And it is precisely because we each have our own methods that we have a more productive discussion, which is why for me this project goes further than merely cooperating.”

“It is striking how quickly we learn from each other, as three people from different disciplines with each their own way of thinking,” Hendriks agrees. “My job as a surgeon often forces me to make quick decisions and then accept the consequences. I cannot philosophise endlessly about whether to do a bypass or not; the patient needs to get off the operating table quickly. It is very valuable to get input from Richard, who thinks very conceptually, or from Antoinette, who asks critical questions like: ‘What does the hospital or society in general think about this?’ But of course, at the end of the day, you are after concrete results.”

“I would normally always start with the problem and look for a solution,” says Goossens. “Antoinette has taught me that there is sometimes no point in investing energy in something that you will soon be writing off as hopeless anyway. I had never looked at it like that before.” “This can be done using disease modelling, where you look at whether a new technology provides added value in light of the diagnostic procedures and treatments that already exist,” explains De Bont. “From a social perspective, you want to improve those areas where patients run the highest risk. That is why it is so important that we are jointly involved in the development from the very beginning. It means we can avoid concluding too late that a solution will not be cost effective.”

Making a real difference in healthcare

Back to that higher goal. “I work with people who have already achieved a great deal in their own field and who already cooperate intensively. We are ready to do it again, they say, and this time we are going to do it right. This illustrates the ambition they have to make this multidisciplinary approach succeed, and that gives a real energy boost,” says De Bont. “I don’t want to become a designer, nor a surgeon, but I do want to learn to understand these perspectives so I can put myself in their shoes. This brings added value to the theme of the consulting room, but it also allows me to enrich my own field of expertise.”

Healthcare must undergo a system change, from reactive to proactive. This cannot be achieved with conventional methods.

Goossens: “We think that healthcare needs to undergo a system change, from reactive to proactive. This cannot be achieved with conventional methods, but we believe that it can be done using convergence. This is also in keeping with the theory behind convergence. That is my dream and we are already seeing it happen in this project. People are now coming to us with ideas for spaces other than the consulting room, where technology can be used to make a real difference. So actually, we are already taking the whole hospital system into account.” “I want only the best for my fellow humans,” says Hendriks. “Anyone can become a patient at some point, and they should always be treated as well as possible. We are not yet using all the tools that are available to us, and this means we are doing our fellow humans an injustice. That need not be.”

CONVERGENCE EDUCATION

In medical care, too, the coronavirus crisis has accelerated digitisation, and this will go much further in the future. “A new kind of doctor will emerge, who will also need to understand what you can do with algorithms, for example. This needs to be addressed in the degree programme,” says Hendriks. Convergence education will be the answer. “We want to train all students in AI skills, because in the future everyone, from designers to policymakers, will need to know how it works. Moreover, our institutions have wonderful lecturers and educational material that we want to share, so that a student from Delft can take entrepreneurship courses at Erasmus, or a student from Erasmus can take design courses in Delft to learn how to work out ideas,” says De Bont. “This does mean that we will be asking directors of studies and accreditation committees to allow more flexibility in the programmes. The programmes are currently reviewed every ten years, but AI is developing much faster.”

Richard Goossens

- +31 (0)15 27 86340

- R.H.M.Goossens@tudelft.nl

-

Room C-3-140

"In the end there is a solution for everything."