As various space probes have reported during 2016 on possible sites in the solar system where it might be profitable to look for extra-terrestrial microorganisms, Beijerinck’s research echoes down the years.

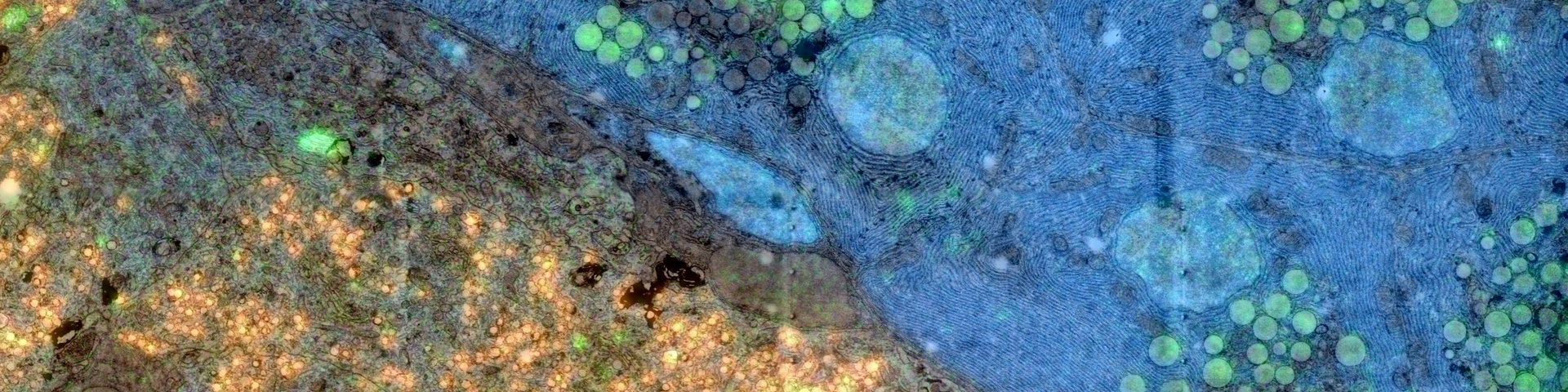

His interest was caught by speculation in 19th century scientific journals that life could have come to Earth in comets. When Professor Onnes of Leiden demonstrated his new equipment for turning gases into liquids, Beijerinck saw an opportunity to test what sort of living cells, if any, could survive such low temperatures. He took a collection of organisms whose behaviour he knew well (bacteria, yeasts, algae and fungi) to Leiden, and froze them in liquid nitrogen (-196°C) or hydrogen (-253°C) for different times and then checked to see if they were still alive and behaving as expected. Some microorganisms could indeed survive the temperatures of space. These were the bacteria, green algae and some yeasts and fungi that were able to make resistant survival forms caused spores. Yeasts that could not make spores and other more complex cells died. Again, he published his results and turned to other research.

Over 100 years later, liquid nitrogen is routinely used to store all sorts of biological material including bacteria and spermatozoa. More complex cells can survive the extreme cold if protective chemicals such as glycerol are added.

Oxygen and photosynthesis

Now that so many libraries have allowed their historic collections to be scanned and made available online, it is possible to find and read original publications. It is notable that back then scientists argued as much as we do today, and researchers had similar trouble persuading colleagues to accept new ideas. This happened when it was first proposed in the early 19th century that oxygen was produced by photosynthesis using light. In the days before electricity they showed the presence or absence of oxygen in a container by testing whether a candle could burn or a mouse could live, and it was hard to prove oxygen production. Beijerinck designed a characteristically simple set of experiments which proved the point.

There are bacteria, mostly in seawater and on the skins of marine fish, which produce their own light as long as they have enough oxygen and nutrients. Beijerinck grew them in liquid with and without seaweed leaves and then, when they were glowing brightly, put the cultures into a dark room without shaking them. When the oxygen ran out, the bacteria stopped producing light. If he then allowed light to reach the cultures, light production resumed in the presence of seaweed leaves, but not otherwise. The bacteria were getting oxygen from photosynthesis by the leaves.

Methods that are still in use today

Like Van Leeuwenhoek before him, Beijerinck investigated anything that caught his interest. He was the first to identify many different microorganisms and to devise methods still in use today. His collected research papers fill 6 books, too many to discuss here. Hopefully the examples presented above have allowed the reader to appreciate how the simplicity of his approach produced clear answers to difficult questions without modern laboratory equipment or, for much of his time, electricity.